Legacy of Logging in the Susquehanna watershed

by BENJAMIN R. HAYES and R. CRAIG KOCHEL

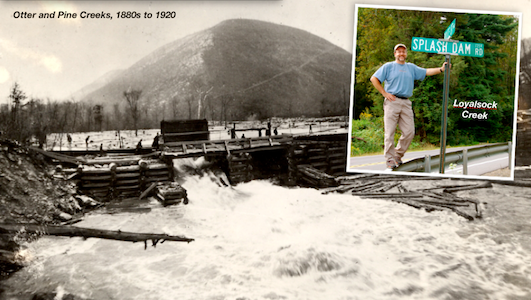

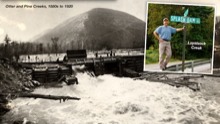

Figure 1. Logging began in early 1800s, as crews began working northward and westward. Pine Creek area, circa 1887.

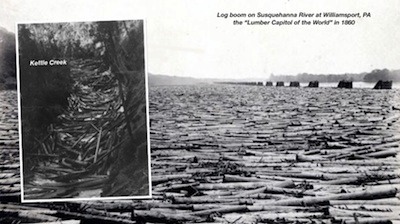

Figure 2. Logs were rafted from the steep tributary valleys into the larger streams that carried them to the Susquehanna River.

Figure 3. Log booms were constructed to shunt the logs to the margin of the river channel, where they could be sorted and separated. Most were sent to lumber mills constructed on the floodplain adjacent to the river channel. The largest and straightest were cabled together to form log "rafts" which were then floated all the way to Baltimore for use as ship masts.

Figure 4. As the result of complete deforestation, this region came to be known as the the "Great Pennslvania Desert."

Figure 5. As a result of better forest management, much of the north-central part of the Susquehanna is once again forested.

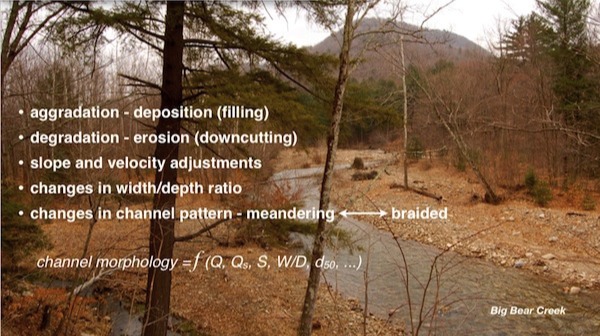

Hydraulic geometries were altered as splash dams, berms, cribbing, and other structures were built. Aquatic habitats were further degraded by channel widening, loss of water depth and velocity variations, and deposition of large bars at artificial constrictions or other areas of energy loss. Over one hundred years later, many streams remain in a protracted phase of fluvial adjustment, with the episodic creation of meanders where artificially straightened channels become clogged with wood, sediment, or ice.

Impact on Existing Stream Restoration Structures

Field surveys of stream restoration structures in north-central Pennsylvania reveal that almost 75% of stream restoration structures are damaged by lateral channel erosion and/or burial by coarse sediments. Thirty-five percent of these structures have sustained significant damage and no longer functioning as intended. Most of the damage occurs as flood-induced pulses of logging-legacy sediment are washed downstream, burying the restoration structures and filling in the pool they were intended to create. J-hooks and rock vanes have sustained the most damage as compared to cross vane structures, with millions of dollars spent rebuilding and maintaining them.

Adaptive Restoration Approaches Needed

Considering these factors, an adaptive stream restoration approach should be used, whereby relic logging features such as splash dams and berms are removed to enable the stream to reconnect with its floodplain, increase habitat complexity, improve flow in abandoned side channels, and permit more uniform distribution of energy throughout the fluvial system. Rather than constrain the channel in a static position using hardened, in-stream NCD structures, restoration efforts should be directed at encouraging the stream to naturally create new meanders, bars, or pools and develop a new equilibrium condition on its own.

Mapping the impact of clear-cutting on the watershed

Composite landscape modeling using Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

Composite landscape modeling using Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

To assess the spatial and temporary variability of historic timbering in the Susquehanna watershed, historic records and maps are being studied, as well as interviews with some of the last living loggers who floated timber to market in the United States - the upper Kennebec River in northern Maine.

These accounts are enabling us to determine relative percentages of watersheds that were denudated and composite those map layers with geologic and topographic information to created 3D geospatial models which can better qualify the susceptibility to soil erosion and delivery to the stream.

Click to enlarge photo

Field investigations are being conducted to locate historic remnants of logging structures in the streams (top photo), not only because they are interesting, but because they often act as grade control structures or sediment traps which are are prone to failure during floods.